An article in the New York Times caught my eye yesterday. The Professors Are Using ChatGPT, and Some Students Aren’t Happy About It read the title. For the past six weeks, I have been coding AI integrations into Innovation. It caught my eye because I have been thinking a lot about AI in education. From the perspective of a teacher, it drives me crazy when my students submit ChatGPT-generated work and pass it off as their own. The cartwheels I have to do as a remote instructor to prevent this are pretty byzantine!

But I am also interested as a businessman. I aim to enliven innovation (and raise its notoriety) by the integration of OpenAI in every aspect of the site. During this feverish coding period since mid-April when we got our API key, I have coded apps that…

- generate multiple-choice questions for tests, reading comprehension, videos, and Jeopardy-style games;

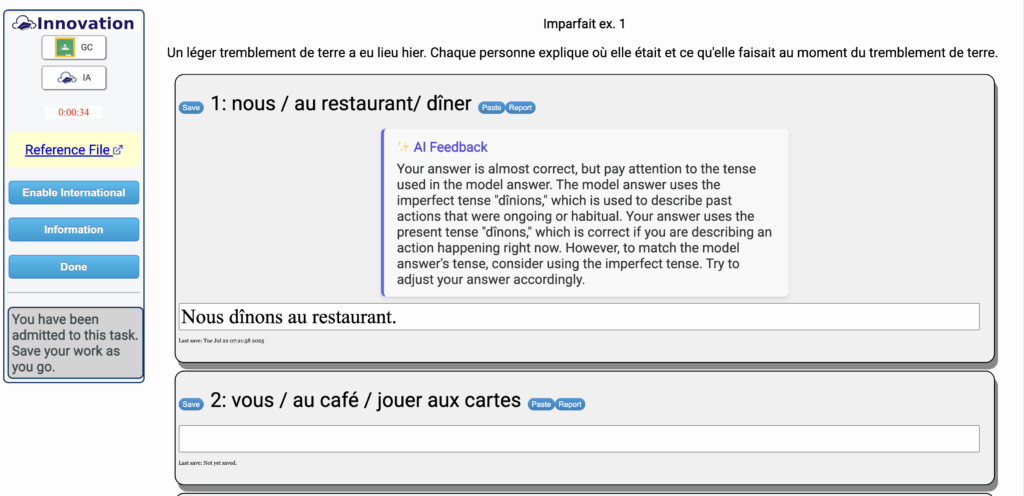

- score short answer responses based on guidelines and model answers;

- score longer essays based on rubrics and instructor-designed guidelines;

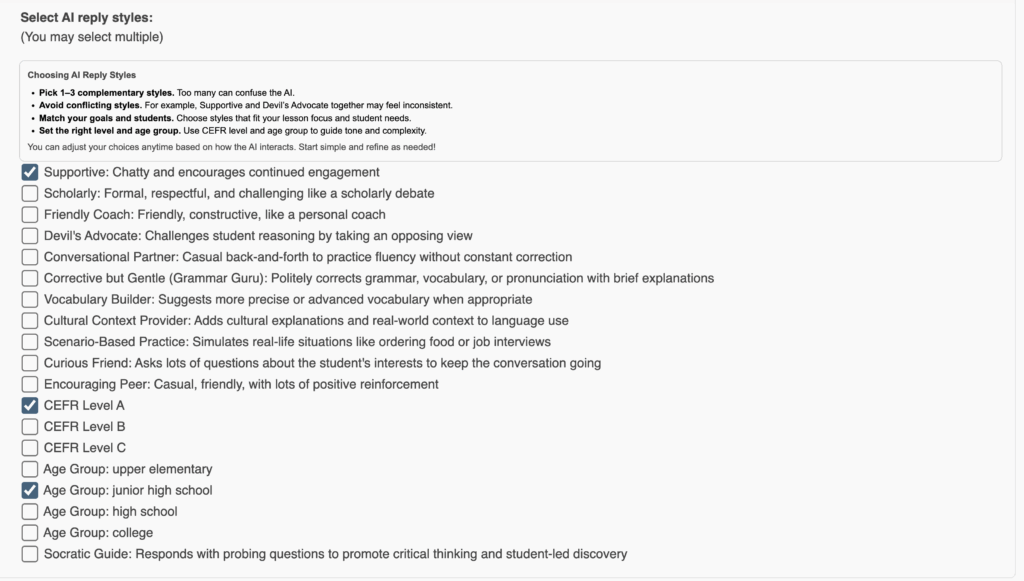

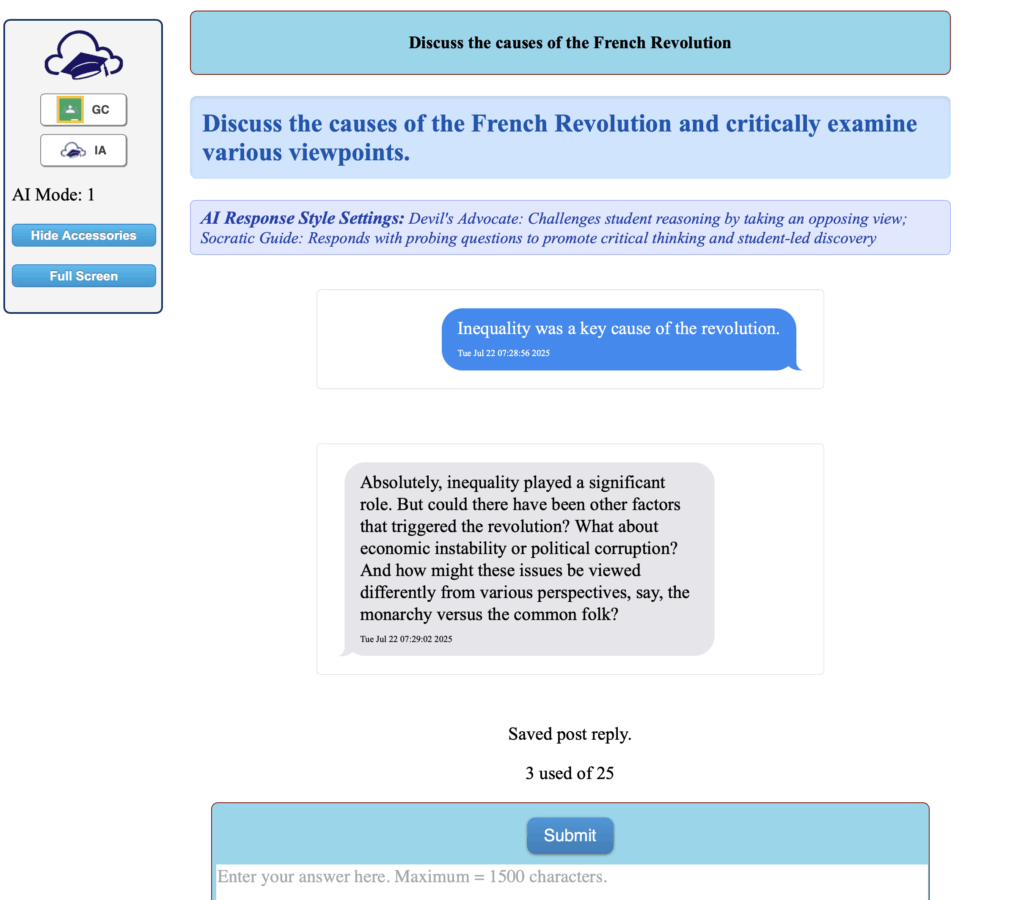

- interact with students in online forum discussions;

- generate composition topics and dictée practices for world language teachers;

- generate custom grammar exercises for world language instructors.

Through the summer, I plan to add some sophisticated AI analysis options for student essays as well as rubric generators and a monitored chat.

In the New York Times article, student Ella Stapleton was a senior at Northeastern University. Her professor had used ChatGPT to generate lecture notes and failed to remove the telltale signs of its origin. Another student found that the comments a professor left on one of her assignments included the chat with an AI to help grade it. One student is suing her university, saying she was paying for instruction from the prof and not from an AI. Are they right to be annoyed?

Readers are no doubt familiar with the Talmud, a central work of Jewish thought composed of rabbinic debates spanning centuries. These debates often wrestle with how to interpret and apply biblical law to real or hypothetical situations. A hallmark of Talmudic reasoning is the use of analogy: to what extent does a current case resemble one already discussed and resolved?

This is the approach I would like to take in arguing specific ethical considerations regarding the use of AI by instructors. I began teaching in 1991. If we assume ethical principles to be fairly static, since right and wrong should probably not really change much, then what was right then is still right now.

In 1991, a public school teacher would have access to a commercially published textbook. This would typically come with a package of pre-made tests and answer keys, workbooks for subject-specific practice, maybe filmstrips or posters, and so forth. It was the common understanding that teachers were not expected to write their own textbooks or even design every one of their own lesson activities.

In 1991, a college professor would typically teach using a commercially published textbook selected for the course. Along with the textbook came instructor guides, test banks, lecture slides, and other supplemental materials provided by the publisher. Professors might adapt these resources, but it was generally understood that they were not expected to create every reading, assignment, or exam from scratch. The role of the professor centered more on guiding discussion, delivering lectures, and evaluating student work than on developing entirely original curricula for each course.

With regard to assessment, my teachers in the 1970s in my grammar school sometimes used a Scantron machine to score those tests where you fill in the bubble. They did not score the tests all by hand. My elementary classes were 35-40 kids to a class in a parochial inner-city school.

When I was teaching social studies here in New York State just before I retired, I was called upon each June to drive far away to meet with colleagues from other districts to score the essay portions of the New York State Regents exams. Two teachers graded each paper and we discussed the merits and the score.

In 1991, assessment at the college level often meant midterms, finals, and a handful of major papers or projects. In large lecture courses, teaching assistants might handle the grading of essays, quizzes, or lab reports, following rubrics or guidelines set by the professor. While professors were ultimately responsible for student evaluation, it was common for them to delegate portions of the grading process, especially in high-enrollment classes. The expectation wasn’t that every piece of student work would receive personalized feedback from the lead instructor, but rather that grading would be efficient, consistent, and scalable.

Returning to the students who are upset with their professors for using AI to generate lecture notes or to generate student evaluations, I think we can reason by analogy as did those Talmudic scholars in times past to ascertain what is right.

My premise, and this is after many hours of working with AI over a year or more, is that at this particular moment in history, the best AI has to offer is to be a rather naive, but sometimes insightful, young assistant. My teachers reviewed the commercially published tests and checked for typos and accurate keys. My professors supervised their teaching assistants, providing them guidelines and checking their work. My AI helpers, who at the moment are ChatGPT and Gemini, need guidance and supervision by me.

Commercially published textbooks, tests, workbooks, worksheets, and the like have been acceptable and welcomed for a century. No one would have asked the one room schoolhouse teacher to publish her own grammar books. No one would have faulted a full professor for having his assistant grade lab reports. In 1991, and this is before the demands of differentiating instruction, the teacher was the creative director of a plan to educate using resources that they had vetted and sometimes using assistants that they supervised. At the time, this arrangement was both normal and uncontroversial.

The introduction of AI as a source of learning or an assessment tool doesn’t diminish the instructor’s crucial role; it amplifies it in the same way a carpenters’ work was amplified by the invention of the nail gun. Just as educators have always been responsible for the quality and integrity of their classrooms, they must now extend that vigilance to AI. This active supervision ensures that AI enhances, rather than supplants, sound pedagogical practices.

Innovation has built all of its AI integrations around a clear philosophy: the instructor remains the expert in the loop. When AI generates test questions, they must be approved by the instructor before being added to an assessment. When AI scores an essay, the instructor sets the rubric, defines the guidelines, and reviews the results before incorporating any of them into the student’s grade. When AI participates in student discussions, it does so within parameters the instructor has defined — including tone, context, and purpose — and under active supervision. When AI grades short-answer responses, it relies on model answers the instructor has already selected and endorsed.

At every turn, Innovation’s workflow puts the instructor in the role of guide and gatekeeper — promoting good old-fashioned professional oversight through the design itself.

The profs who failed to properly read and edit the course materials or assessment comments are to be chided for editing poorly. But the expectation that students have that instructors be the author of all of their course materials is born of an age when technology makes this at least theoretically possible, although not practically so. The expectation that no assessment will be outside the hand of the instructor is a new fashion, also imagined in a context of hyper-alertness to AI usage. One professor noted in the article was criticized by the student for chatting with the AI about writing the critique of the student’s work. But this is precisely what a professor might do with a live assistant in days gone by! The difference is that the student of the past would have no knowledge of the discussion.

One of my remote students this year had nothing good to say about one of her teachers. She cited the example of the fact that her teacher got her powerPoint slide shows from ChatGPT. If that powerPoint were of poor quality or included incorrect information, I could agree. Where this student goes wrong is in thinking that the general notion of getting learning resources elsewhere is illegitimate or unprecedented. The wrong would be in presenting shoddy or incorrect information, not in failing to be the author of everything.