AI assistance and translators such as Deepl and Google Translate are very accurate and useful tools. When I assign my French students certain tasks, I expect they will use these tools to help them just as I would have expected students in-person thirty years ago to use a French-English dictionary to help with spelling and new words on certain tasks.

The problem is that the temptation to just have the AI generate the work is a strong one. It is important for remote instructors to place obstacles in the way of this practice, which not only undermines the student’s training but represents an ethical pitfall.

Imagine this scenario: an online AP Spanish class where major assessments are take-home tasks like essays and video-recordings of presentations. Using the traditional paradigm for this assignment, the student is given guidelines and due dates and a rubric with a graphic organizer. The instructor provides all that. Then the due date comes, all the work is in, and the instructor begins to review the work. What impressive vocabulary! What elegant grammar! And yet, reflecting on the spontaneous language generated by these same students in video-conference live sessions, it is hard to believe that this work could come from some of them.

All of my remote courses begin with a training film of sorts in which I explain the concept of academic integrity and ownership of one’s work submissions. I explain that it is expected that students will learn all of the new words they incorporate into their work submissions so as to maintain ownership of the task. I demonstrate using a translator properly and improperly.

A very useful strategy is one I have used since in-person days decades ago: simply ask the student the meanings of the words in their work that I suspect they do not know. In the remote learning context, this can be difficult to arrange, since there is no easy way to pull a student aside during class and conduct the interview about their work. That’s where Innovation comes in.

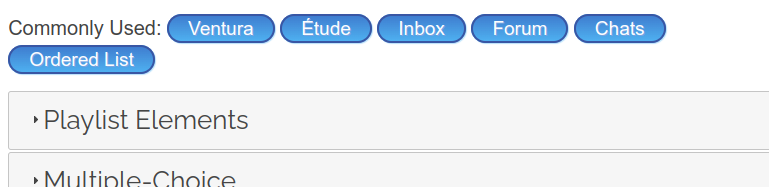

It only takes a few minutes to select words and phrases from the student’s work submission that I believe they do not likely know. I select seven to ten words or phrases and I generate a short answer translation quiz using Innovation’s Quick Short Answer.

I enter a title, maybe set the category, and enter the words with English first, an equal sign, then the French.

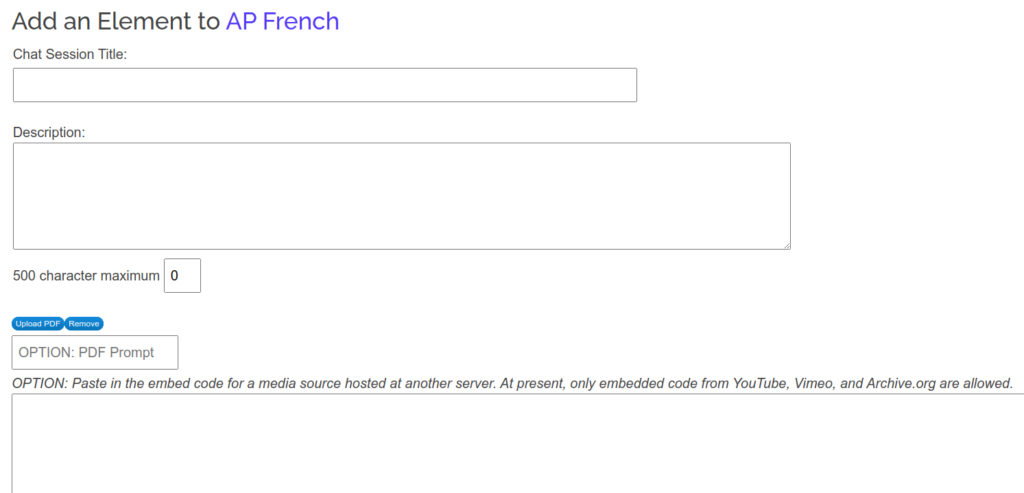

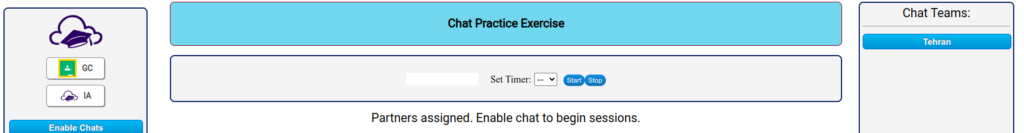

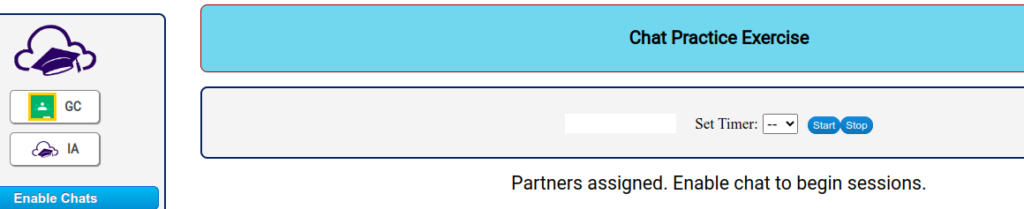

Innovation’s app separates the word from its meaning by the equal signs. Once I have generated the quiz, I access the quiz Master app. I set the time limit to 1 minute for 7-10 words and I turn on the high security.

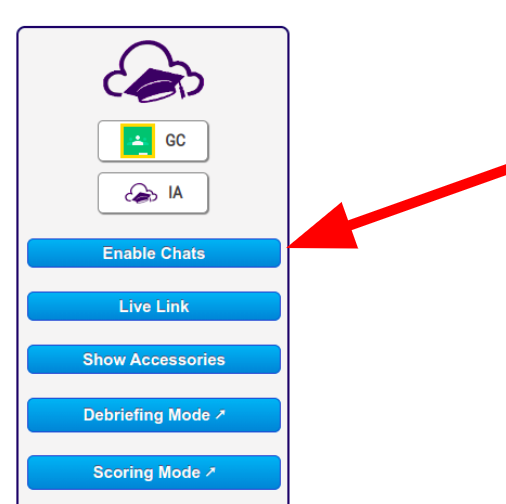

With the high security on, the assessment will submit and lock the student out if the student leaves the window to click on something else. Only the teacher can re-admit student to the quiz. The window resizes to full screen when the student starts the task and if they resize it smaller, the proctor records it. The proctor also records start time, how much time spent on the questions, whether text was pasted, and more.

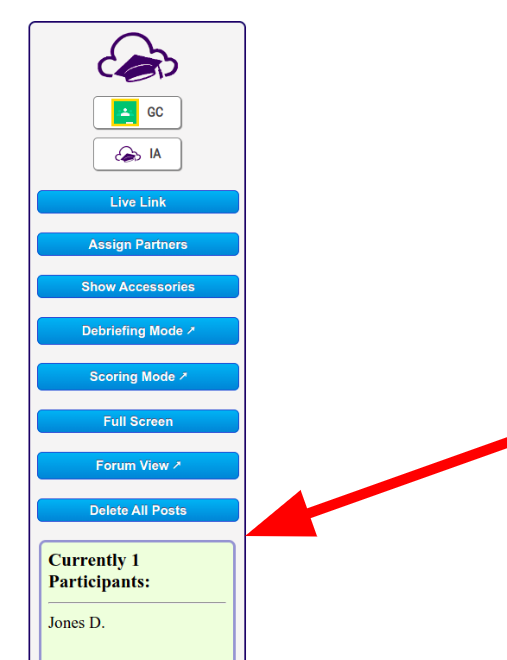

As a final step, I lock the quiz up to only certain access codes. This allows control of how many times a student can restart the task. Simply select the Task dropdown from the playlist and then select Lock. Instructors can view the access codes from the Task dropdown or can generate one key by clicking the One Key button next to the title.

Sometimes, I will ask that the local facilitator proctor the student during the quiz so that they cannot look up the words on their own device.

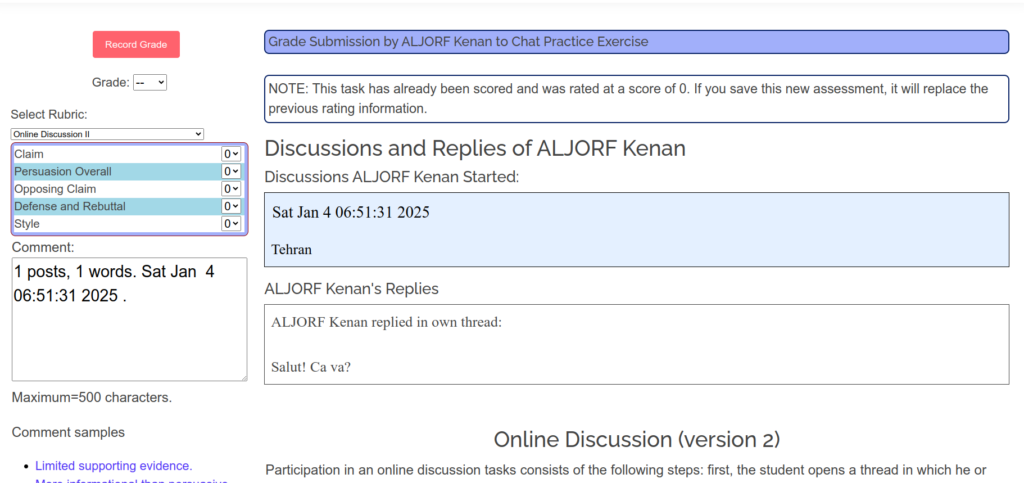

So now what does one do with the results? When first introducing this strategy to students, I explain that it will not affect their grade “this time” and that it is a good reminder to make sure students have full “ownership” of their work. I may randomly select students for this verification, or if it’s a small class I may include it as a portion of their grade for a task and send one to everyone.

It’s not necessary for a student to get 100%. I usually take the quiz first to test it out; to see how many I can do in 1 minute. Even if they do not get 100%, I can learn a lot from their responses. For example, one student got 44% right of 8 and did so by skipping around. I interpret the skipped words as ones she forgot and intended to get back to later. Another student only got 33%. I interpret that as definitely being a sign that his work submission had too many looked-up words he did not know. I let him off with a warning this time and a reminder about academic integrity and ownership.

I once had the experience of taking over a class part way through the year. No structures had been in place to discourage inappropriate use of AI. The grades were all outrageously good. Some students were rarely in attendance and only handed in work that was graded. They did this work using AI, so it was no real effort. This really is a terribly corrupt system, especially given that there are students in nearby schools taking in-person classes who have to really do the work for their marks. There are honest students with good attendance who have lower grades for their honesty. It was an AP level course. Now, you might argue that the students would not possibly be ready for the AP exam if they took the course this way. One would think that would deter them from cheating. But upon reflection, it’s clear that having a 98 in an AP class on one’s transcript, even if one only scored 2 on the exam, could be valuable for college admissions considerations. So, no, it does not deter them.

Remote learning has enormous potential. I have great confidence in it. We instructors, we need to learn how to maintain the same standards as we had during in-person sessions. We cannot allow a situation to arise such that students in remote classes can just become pass-through vehicles for AI translators that do all their work. That situation would become a sort of scam. In part 2 of this topic, I will present a strategy for teaching composition in this new world of AI-assisted homework.