Upon retiring from full-time public school teaching in 2023, I took part-time working teaching French remotely. Teaching via video conferencing turns out to be a terrific method and a very satisfying work!

Being also a web developer for a platform designed for remote teaching and in-class 1:1 designs, I was inspired by this work to begin developing a set of applications specifically for teaching world languages remotely.

I always loved improv and when teaching social studies or French in my career, my students and I enjoyed role play as a learning tool that was fun and meaningful. My practice was to incorporate many exercises to develop conversational proficiency using improv or semi-improvised “scaffold” dialogues.

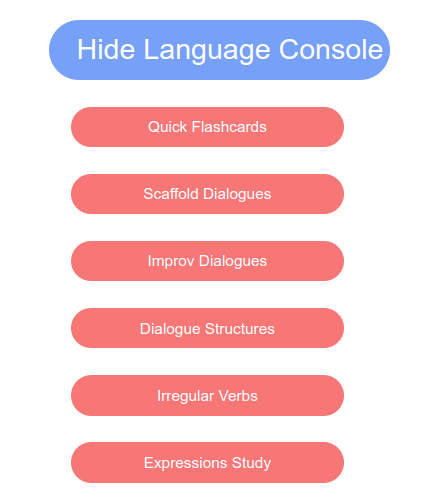

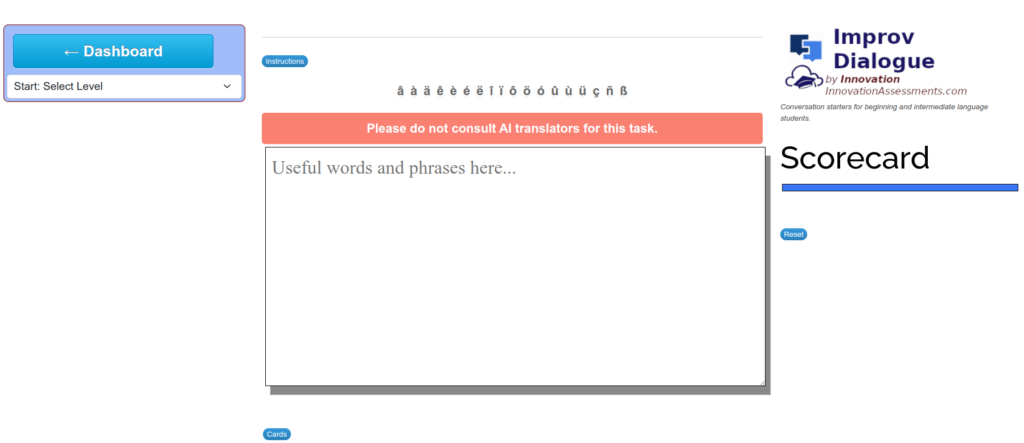

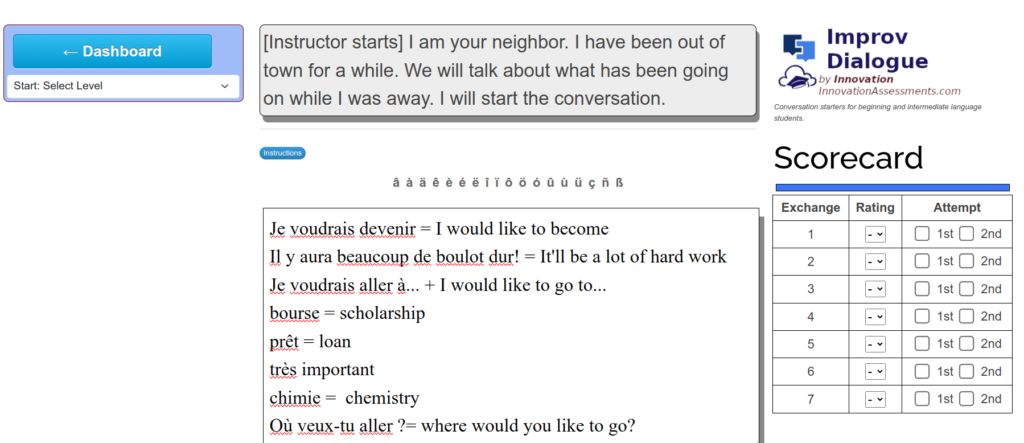

The improv app at Innovation is now well developed. This app is available to subscribers only right now from the Language Console of the dashboard.

The teacher shares the screen in a remote teaching situation (or in-person, displays the screen in class). The first thing is to select the proficiency level. I use the CEFR descriptors.

A notice appears in red in the center advising students not to use AI while participating. This was sometimes an issue for me with some remote students, who quickly consulted Google translate instead of improvising their own contributions to our conversation. Teachers can remove this notice by clicking in.

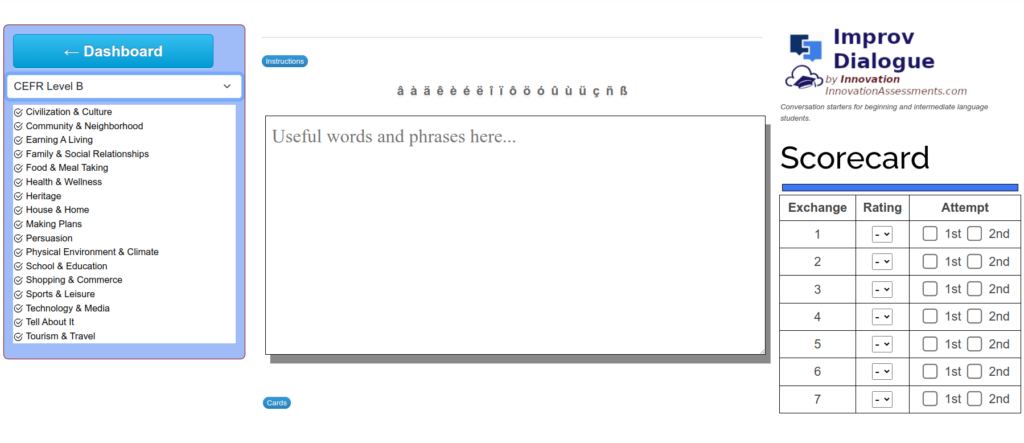

Once the difficulty level is chosen, the teacher can select from the available conversation themes. These correspond to typical topics taught in world language classes that employ thematic units as the method. The reader will notice in the graphic that a scorecard appears on the right. The scoring method is that used in speaking tasks on New York State world language assessments and instructions are available at the click of a button.

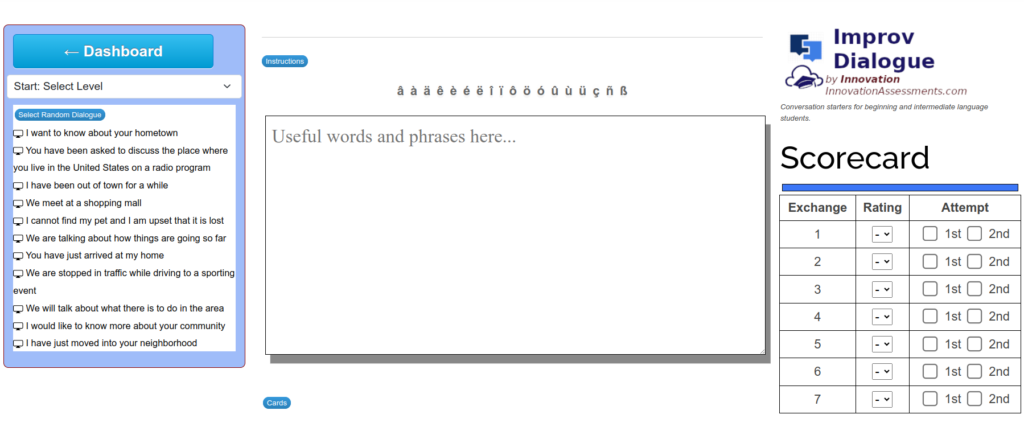

Once the teacher has selected the theme, a set of possible dialogues appears.

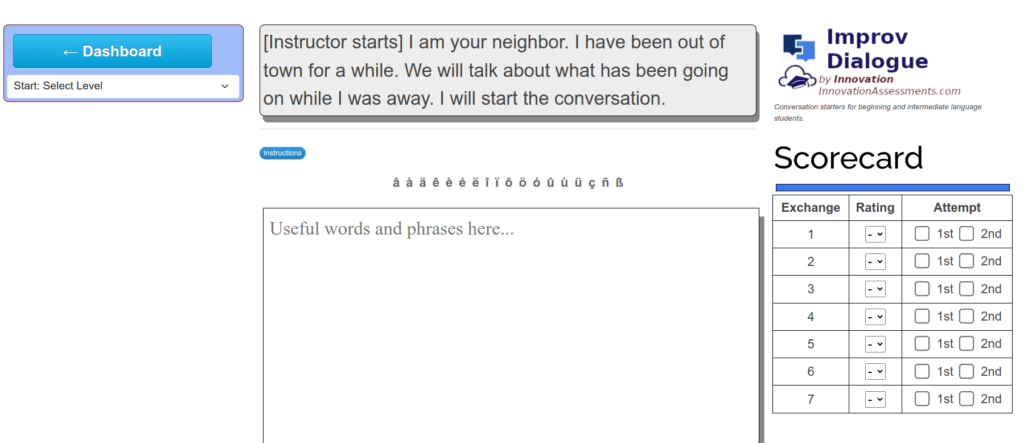

Upon selecting the prompt, the conversation can begin. As the dialogue proceeds, the teacher can track the attempts and utterances in the scorecard on the right. They can award 2 points for utterances which are comprehensible, appropriate, and make no surprising errors for level. the can award 1 point for utterances that are not quite right for that student’s expected proficiency. The app automatically calculates the grade.

Now what I like to do is to use the large textarea in the center to provide useful words or phrases that the student asked for or needed during the dialogue.

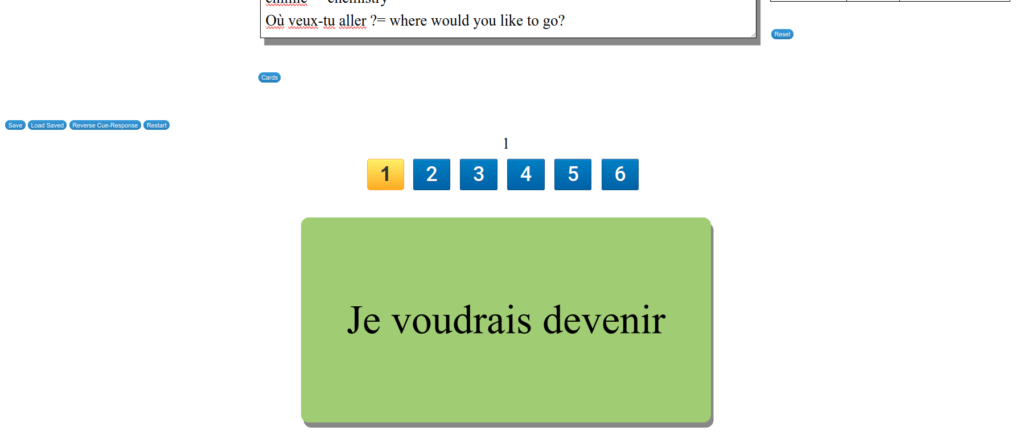

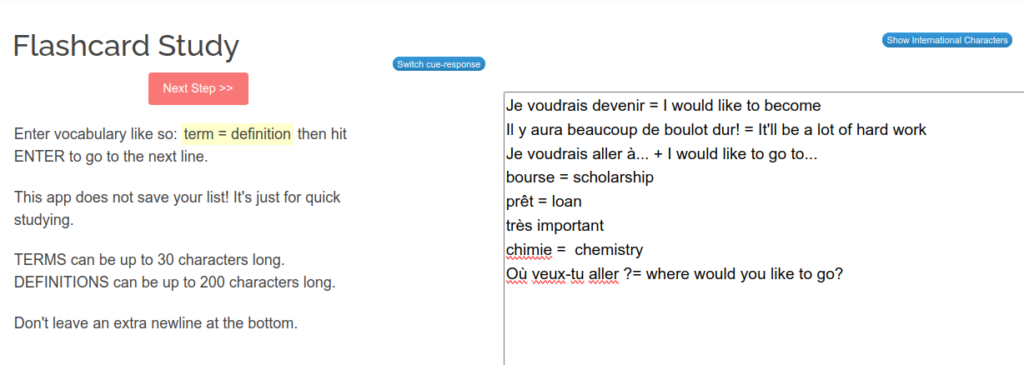

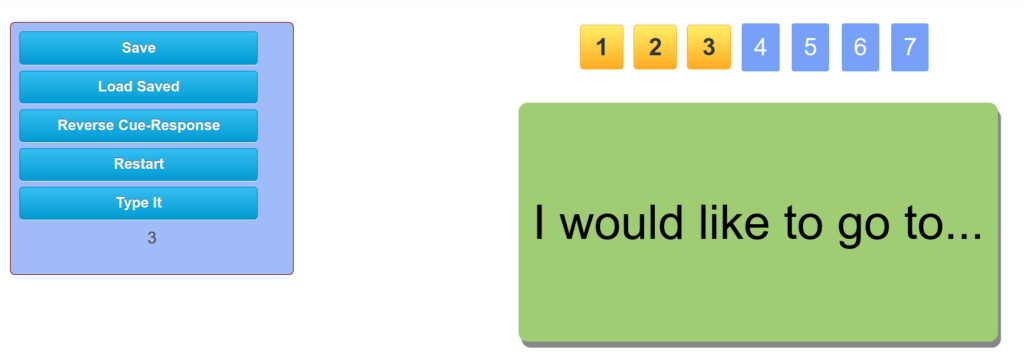

List the expressions with their meaning separated by an equal sign. Here’s why: the Innovation flashcards app has been integrated so that we can study the phrases! Scroll down just a wee bit and you will find a small button called “Cards”. This will extract those phrases and arrange them into flash cards for study!

My practice is then to give students a copy of that list via email or in their lesson notes. They can themselves use Innovation’s Quick Flashcards app to generate their own drills for later.

The development of the improv app at Innovation has been a particularly exciting work. By incorporating elements of improvisation and conversation scaffolding, I’ve aimed to make language learning both engaging and effective for students in remote teaching contexts as well as for in-person learning. The app’s integration with other features such as proficiency level selection, themed dialogues, and real-time scoring ensures a comprehensive learning experience.