Teaching composition in a world language is always challenging to organize and execute. In my experience, the best lesson series in supporting the development of strong composition skills consists in the following:

- Students should have limited access to outside resources in composing their work. It’s too tempting, especially now, to use an AI translator.

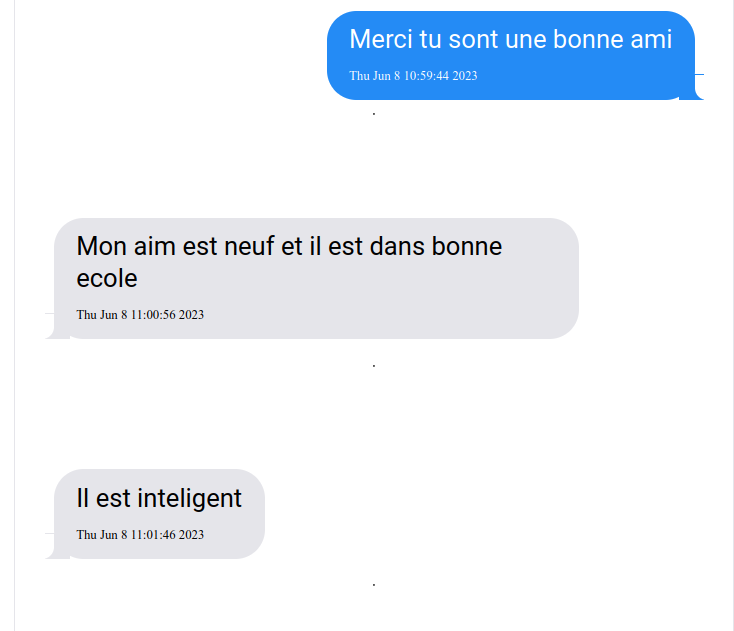

- Students should learn to avoid translating in their head from English to the target language. Instead, they should learn to “say what they can say, not what they want to say.”

- Assessment should provide a clear and understandable measure of the value of the work product and a clear path to remediation for next time.

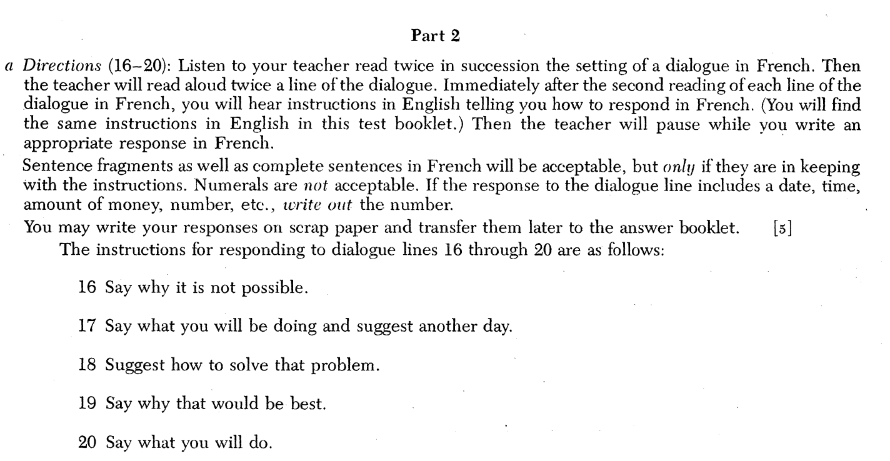

I started teaching in 1991 (I am now retired). Back then as a French teacher, the method for assessing student compositions involved marking off each clause, identifying each error, and checking whether the clause was comprehensible (to a native speaker accustomed to dealing with foreigners), appropriate (such that it built on the theme coherently; it “fit”) and had good form (no more than 1 error in grammar / conventions). This was abandoned in the later 1990’s for a rubric that was more consistent with other New York State Regents examinations of the time.

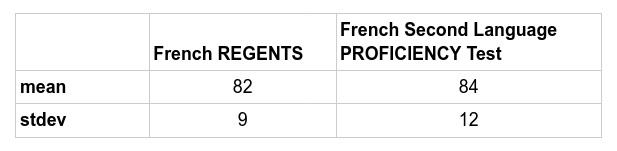

I think the only thing I like about the rubric assessment was that it considered the variety of vocabulary used. Otherwise, the rubric did not really satisfy what I wanted in an assessment for composition work and this rubric was far more subjective than I was comfortable with.

Teaching remotely, I wanted an app that met my criteria for supporting composition skills in the target language.

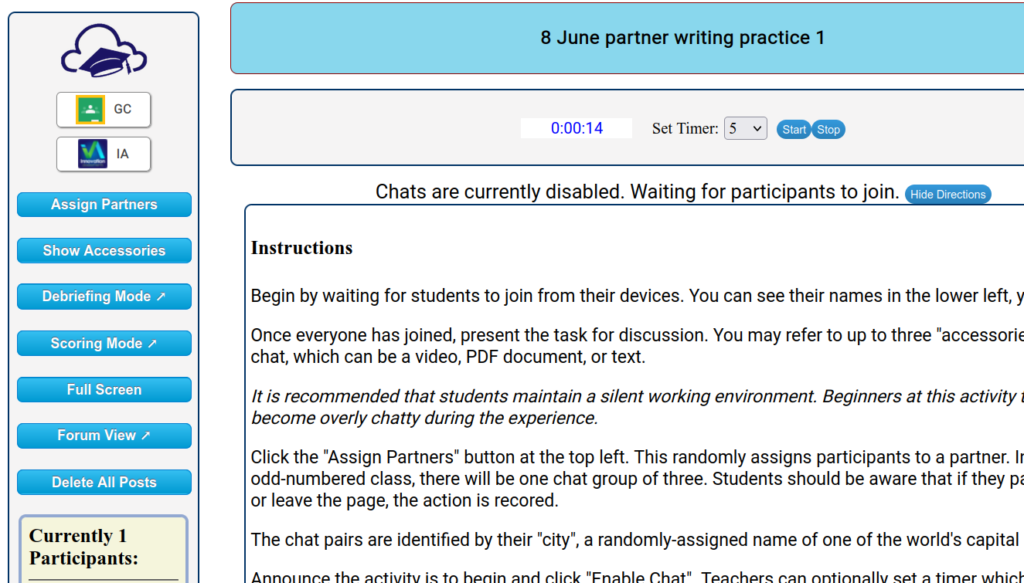

The first challenge was to limit the use of outside references. For this, I coded a sort of algorithmic surveillance AI that I called “proctor”. Proctor consists of a series of JavaScript functions that record when a student has resized a window, pasted text, “left” the page, or restarted the task. These actions are saved and reported to me when I assess the students’ work.

In the remote teaching situation that I enjoy at present, students do their compositions unsupervised for homework. The proctor allows me to curtail student access to other tabs because it announces in red text on the page whenever any of these “suspicious” actions occur. Although students may indeed use their phone separately on the side to confer, I can also check later in our debriefing by asking whether they know the leaning of one phrase or another.

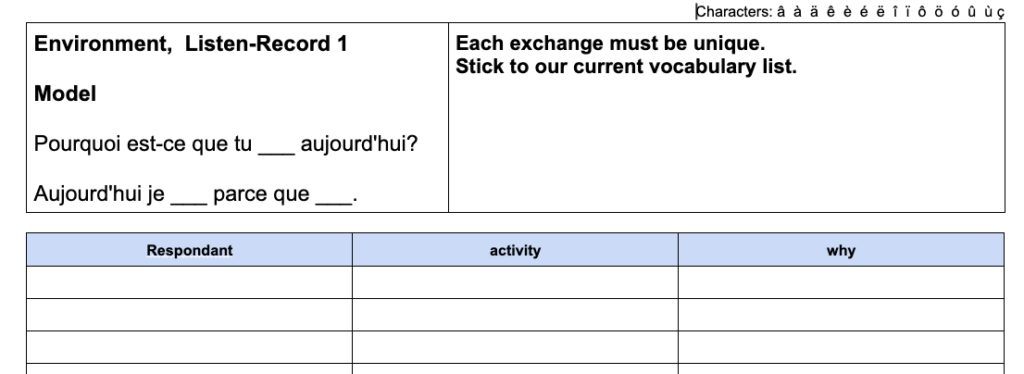

The composition app for world languages allows me to present students a word bank. The word bank can be an antidote to mental translating because students can be taught to weave together meaning from words they have rather than get caught up on words they don’t.

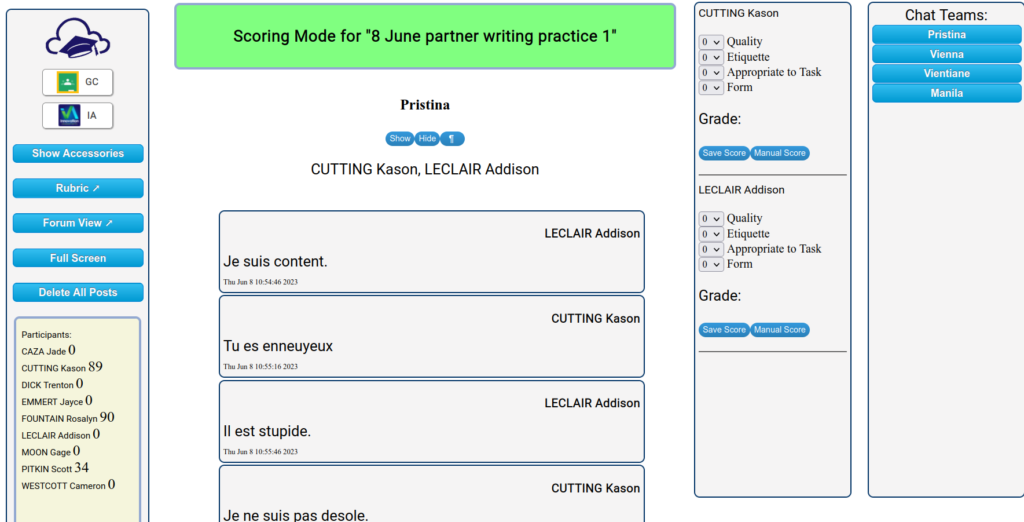

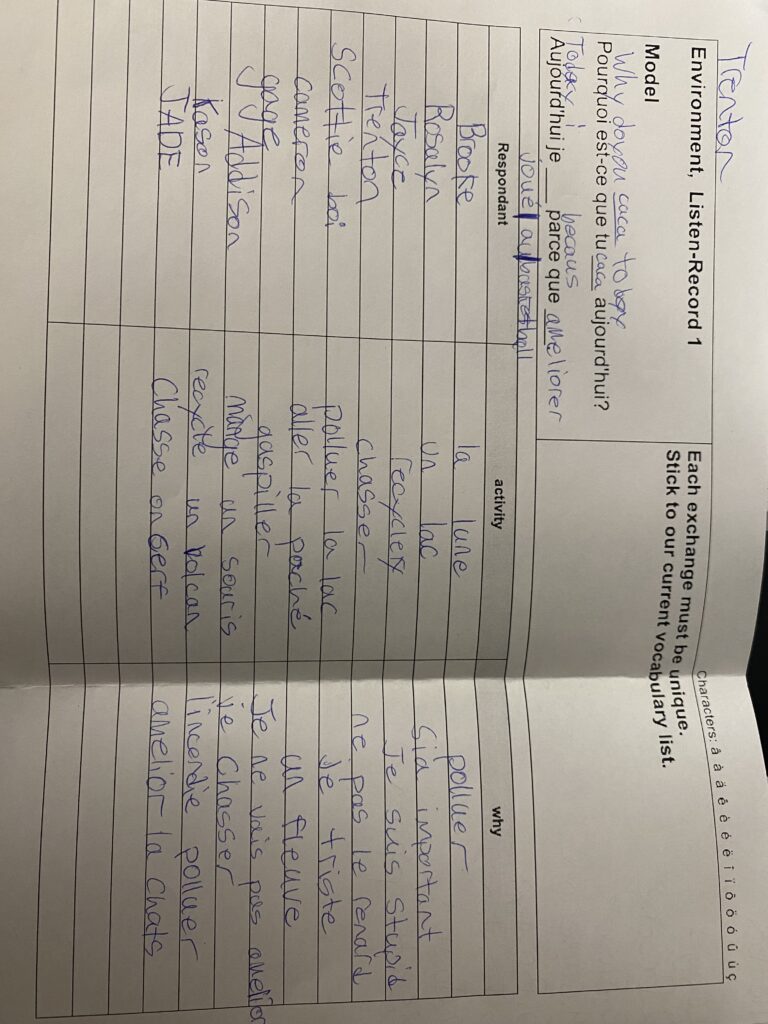

The assessment process in the composition app works as follows. The instructor:

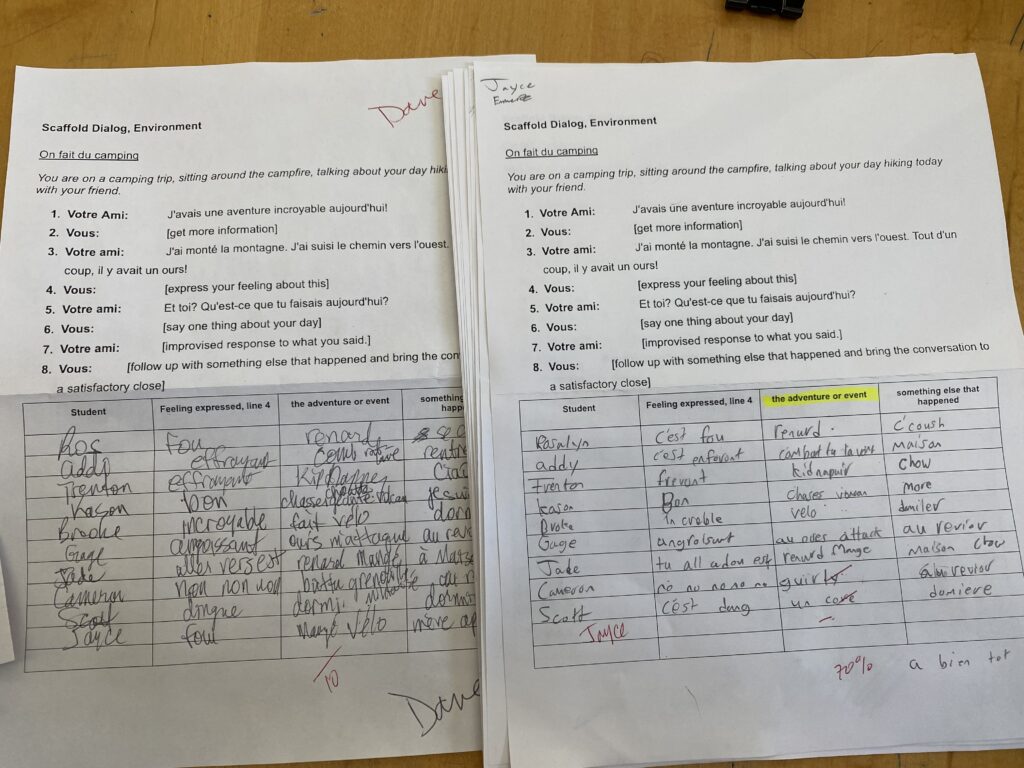

- marks off the clauses for evaluation.

- highlights each error.

- assesses each clause for comprehensibility, appropriateness, and form.

- assesses the whole composition for vocabulary “richness” (10% of the score).

This process lends itself well to debriefing because the errors can be studied directly and are readily observed.

A 21st Century Learning Space

The composition app is a 21st century learning space.

Training wheels are temporary assistive devices for young people learning new things. They are a modification to the program that is usually temporary; a scaffolding that brings students upward in the zone of proximal development. The composition app has space for a word bank to support composition from known lexical items.

Guardrails are there to protect us from error, safety features along the road at dangerous points to avoid a pitfall. The composition app includes an algorithmic AI to monitor student activity and discourage assistance that would not be appropriate.

21st century learning spaces lend themselves to debriefing: they are designed such that the anonymous presentation of teacher-selected student work is easily generated for debriefing. The composition app is readily shared with the student and the assessment page is clear and easy to understand. When I debrief these, I paste the student composition into another screen and go over the relevant errors.

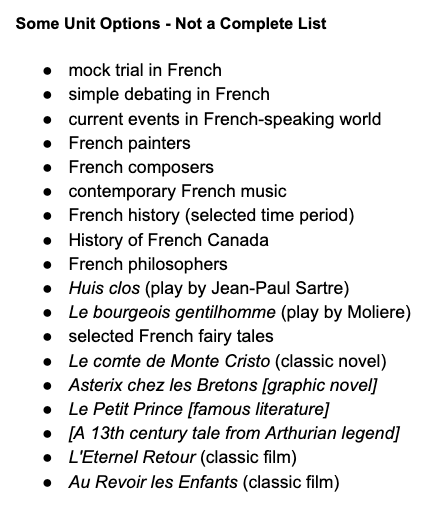

21st century learning spaces are a Swiss army knife. Such collections of applications serve many functions from the same core. The composition app saves the composition prompt in a database whose elements can be re-used.

21st century learning spaces are those where the teacher rules the roost and student privacy protection is a high priority. Locus of data control is with the teacher. The teacher can view the composition as it’s being composed and has ownership over the final product.