The best way to learn to write well is to write and review the selected errors with an instructor for learning and practice. When I was teaching in-person, I would assign a composition in my French classes at the end of the unit to be done without any notes or references. I would then gather up the mistakes students made and we would commit to study them and learn to correct them. It is a great method to promote accurate and fluent writing in second language.

Teaching online, however, my work submissions from students in free-write compositions, even in one-on-one classes, were often AI-generated to such a high degree that the students really could not claim ownership. In one-on-one lessons, I did not always let on that I knew what they had done or sometimes I just made light of it. I could turn it into a useful exercise by asking the student to explain some tenses they used or some structures. But it is not the same. I felt like going into remote learning I had lost an important language training practice.

I have been enjoying success with a new kind of exercise for teaching composition. I will not claim to have invented it as surely someone, somewhere, has already done so. But I do say this method is not one I have seen or used before.

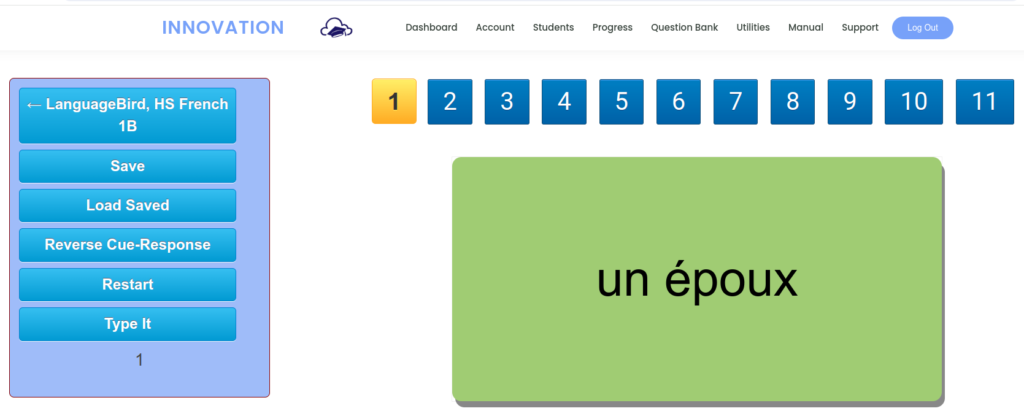

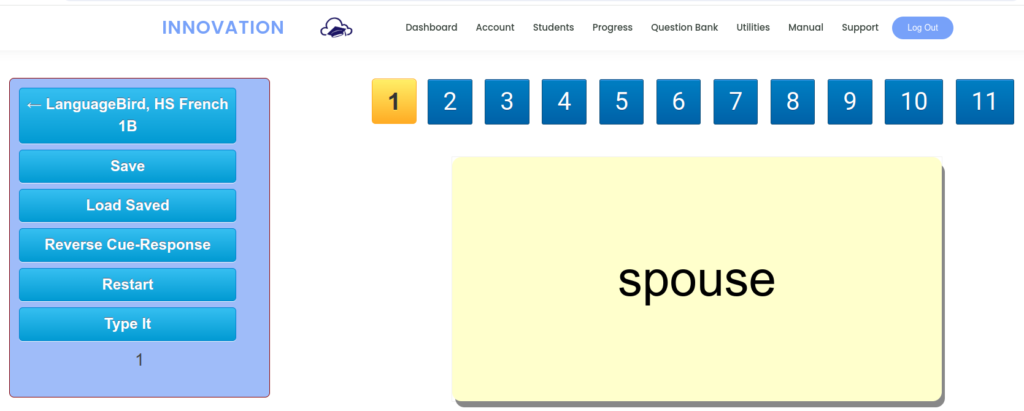

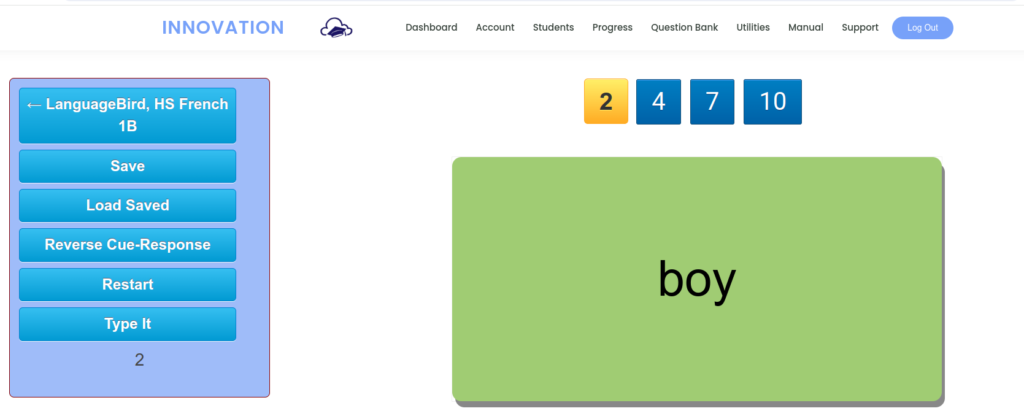

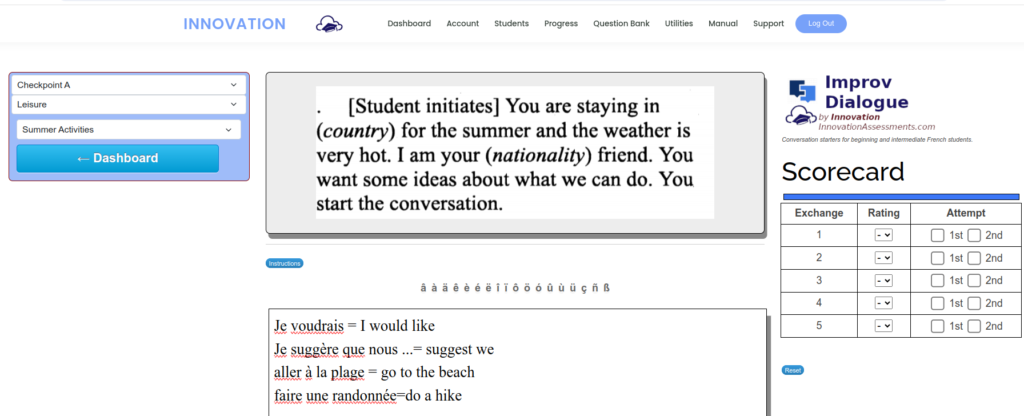

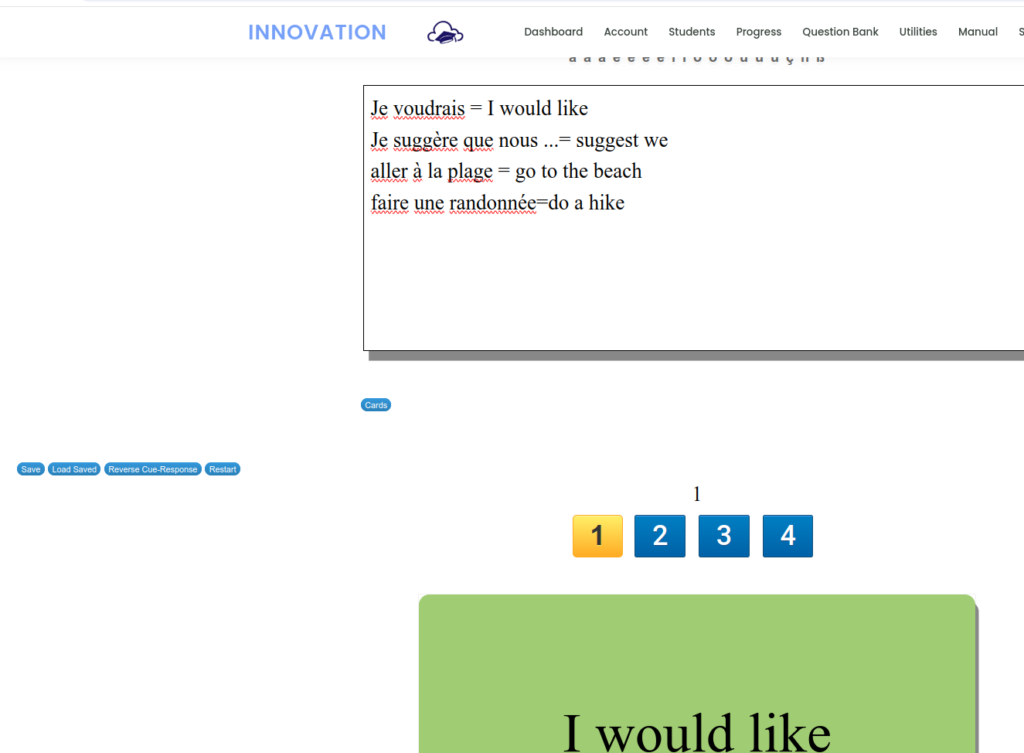

The student is presented with a series of prompts that constitute a composition in the target language of two to four paragraphs. The Innovation app presents them with one prompt at a time.

The prompt is a set of sentences that are in random order. One task for the student is to read these and arrange them in the best order. I design these using the unit theme vocabulary, so it is good practice in reading comprehension as well as in composing cohesive writing samples.

Often, especially for younger learners, I remove a word from each sentence and put it in a word bank. So now students have to not only rearrange the sentences, but they need to fill in the blanks based on context. Again, it’s a support for reading and composition.

Another strategy, especially for advanced learners, is to display the verbs as infinitives for the student to conjugate. In addition, I can remove the transitional phrases and ask students to supply them. Sometimes I include a prompt asking the student to add one sentences of their own, perhaps by providing an example of what it being discussed.

The prompts are displayed to students as images and not plain text, which creates an obstacle for those who would want to paste it into an AI to do the work for them. Displaying the prompt as an image file forces the student to write for themselves. An added benefit is that this promotes more lengthier writing for students who normally write way too briefly.

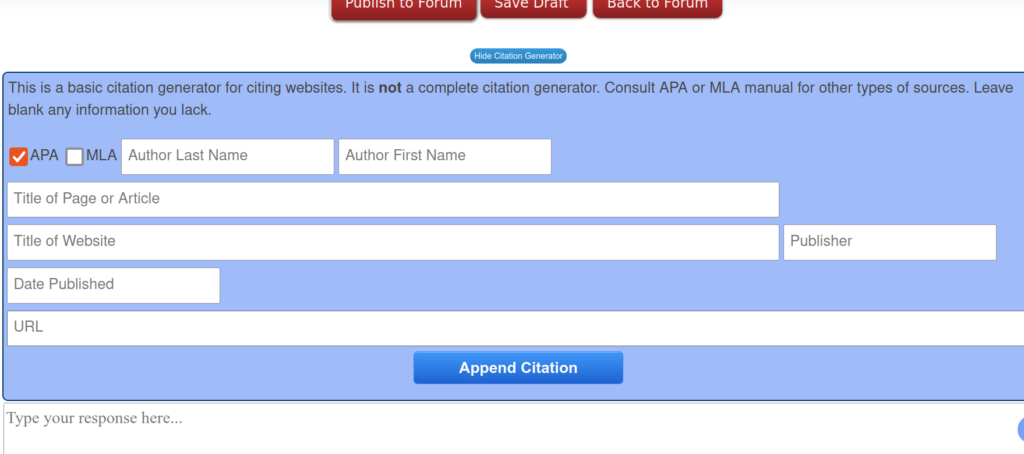

Innovation makes this easy! I select the “Single Short Answer task” from the Short Answer controls. I add each prompt with the answer key.

Then I add the screenshot of the prompt.

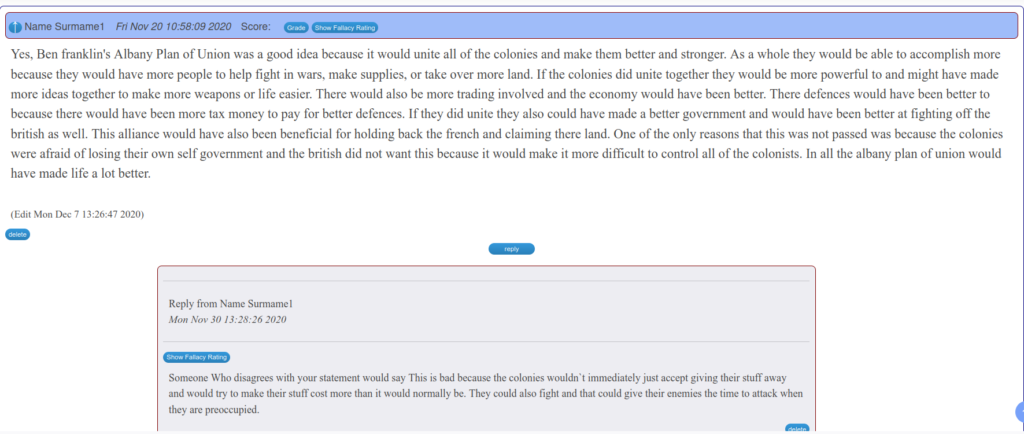

The short answer app at Innovation lets me place obstacles in the way of AI use and helps me generate practice exercises that help students develop their composition skills in the target language. Students have practice seeing and copying language in its standard and correct forms. They practice reading comprehension and the current theme vocabulary. They can rehearse transitional expressions and devising cohesive compositions. Prompting students to “Add one sentences of your own” prompts synthesis.

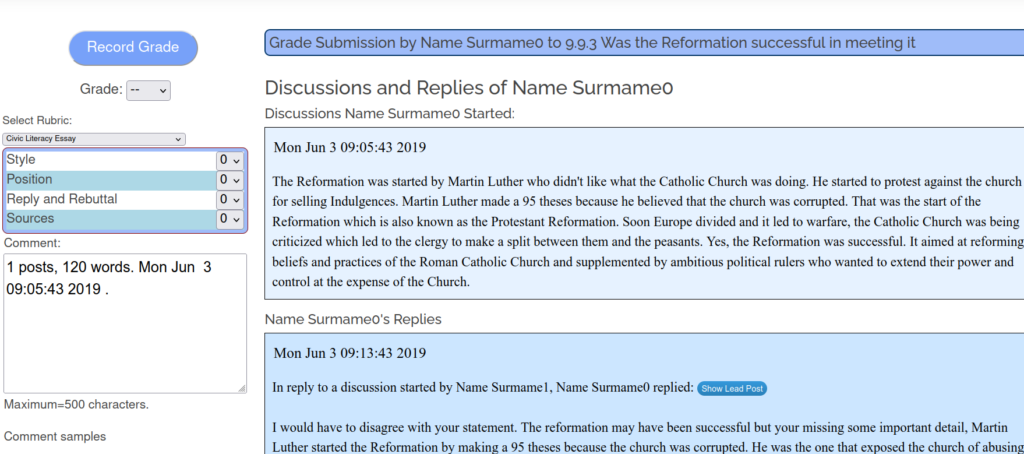

The tasks are easy and quick to score. From the course playlist, select Task, score One Student, and easily compare the student’s response to the answer key.

Although my preference is still for a free-write composition assignment, I can see many advantages to this one. I began developing this task with a mind to place obstacles in the way of student misuse of AI translators to do their work. I think I ended with an exercise that may arguably be actually better than free writing.