How to promote academic integrity in remote learning and in-person classrooms with 1:1 laptops

My interest in devising 21st century learning spaces really took off during the pandemic. The school district I was working in at the time had already moved to get all students in middle and high school Chromebooks and all classrooms had interactive projectors (“Smartboards” at the time). I had the advantage of having two perspectives on this, one as a former IT guy (I was district technology coordinator in a few schools in addition to my full-time teaching role and I was a certified network admin) and one perspective as a teacher. I knew we were just co-opting office productivity software for classroom use and it just was not cutting the mustard. Most notably, in our move to digital learning spaces, we lost some of the guardrails we used to maintain academic integrity.

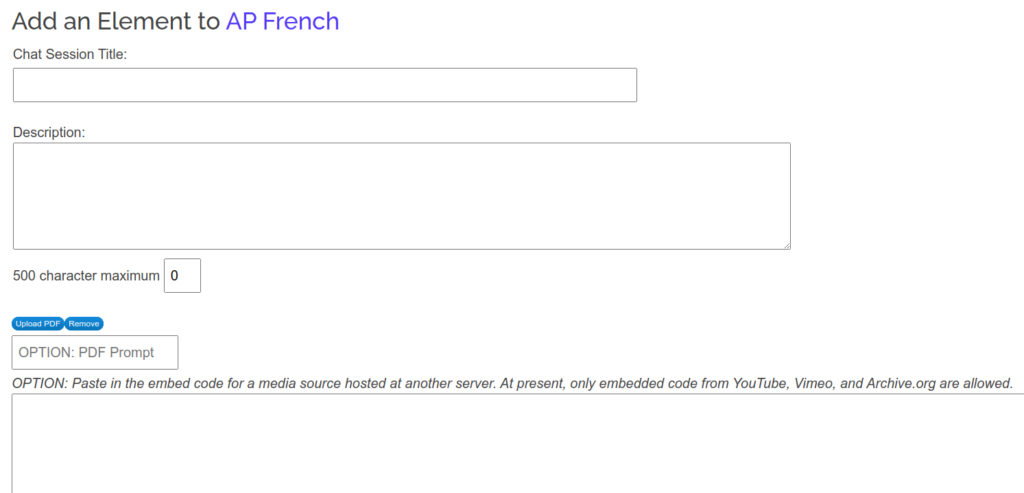

What I mean by digital learning space, a term I use interchangeably with “21st century learning space”, is a software application hosted on the internet in which students conduct their studies and teachers conduct their lessons. My phrase “maintain academic integrity”, well, that mostly just means it was harder to keep kids from cheating.

This situation has come a long way since that time. Schools use a number of content filters, tracking apps, and screen monitoring software that is quite effective. But there are still gaps and I would put Innovation forward as a remedy to fill some of those gaps. Innovation plugs pretty easily into any LMS via convenient links.

Security Tier 1

The apps at Innovation fall into several functional tiers. Tier 1 entails just recording and reporting student activity on the apps. The Proctor is installed to monitor student activity as they interact with the digital learning space. It logs the following student actions:

- started task

- left the page

- returned to the page

- pasted in text

- resized window

- saved work

Tier 1 security on the short answer has some added records, such as notification when student deletes all of their response and the size of newly saved work compared to the answer it replaced. This was devised in response to a student who used to delete all his work and then claim he needed a retake because the system did not save. 🙄

In addition, the short answer task does not allow some other actions such as right click, spell-check, grammerly, activating dev tools, and the like.

Tier 1 security is applied by default on the Etude, short answer, grammar, world language composition, and media proctor. The media proctor records:

- video started

- video paused

- left page

- returned to page

- duration engaged with video

At the tier 1 security level, the idea is to record detailed information about student engagement and to provide two things: 1) messaging to students showing what is being recorded and 2) reports for instructors who may or may not wish to take action on what the proctor saw. Just telling students that their actions were suspicious (like pasting in text) can serve to deter some mischief.

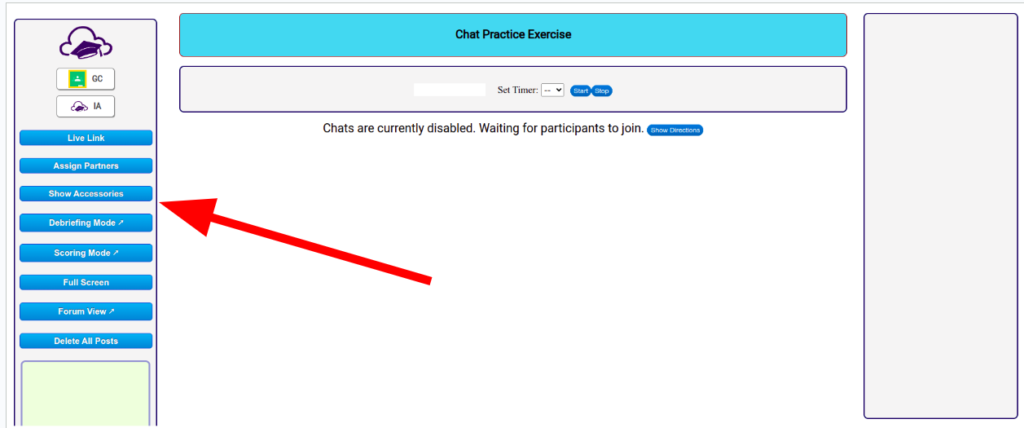

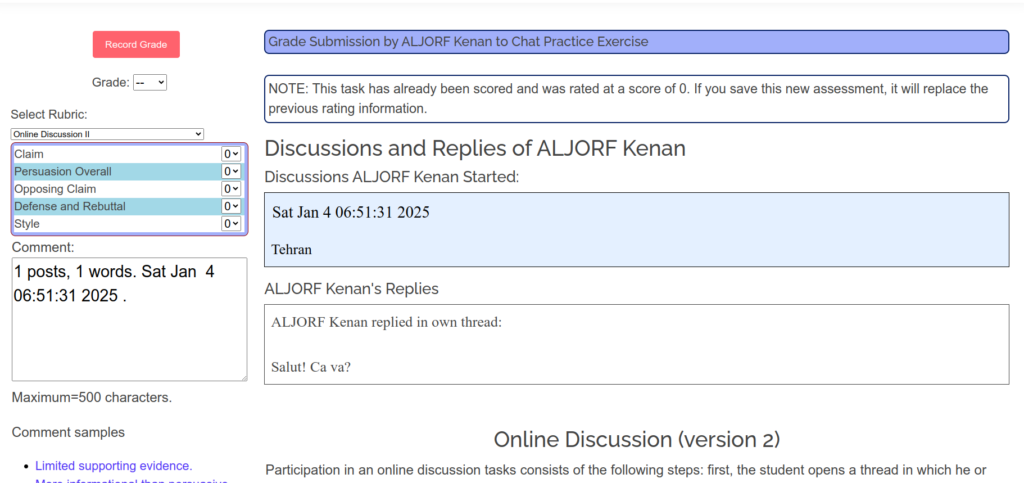

Tier 1 security is enhanced by the new Monitor app. This allows teachers to view student work progress on a task in real time (well, there’s a 10 second delay after student saves, but it’s still pretty quick). Monitor is available for short answer, grammar, world language composition, and Etudes. The Monitor displays all students who have saved work to the task. Select a student, and their work is shown. The proctor summary shows how many times students are doing each of the proscribed actions.

The multiple-choice app by default has security tier 2.

Security Tier 2

Tier 2 security is enabled by the teacher on the Master page for a task. the master page is accessed from the course playlist under the Task dropdown. Select “Modify test” from the controls at the top, and check the “High Security” checkbox.

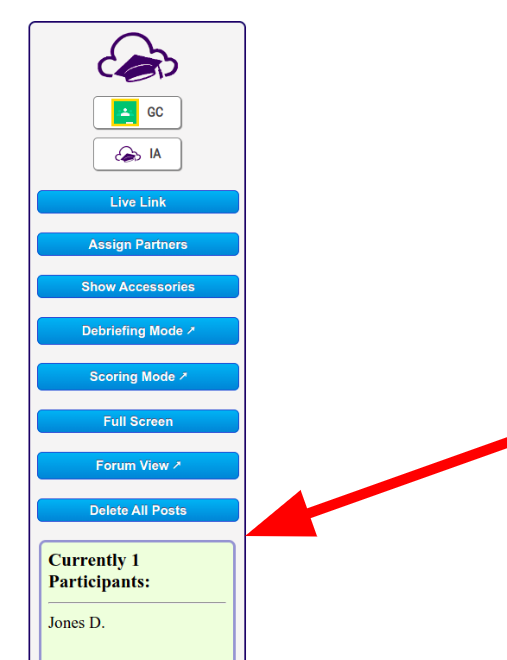

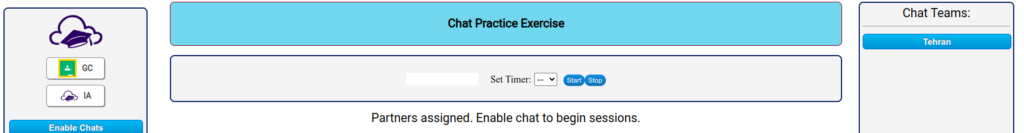

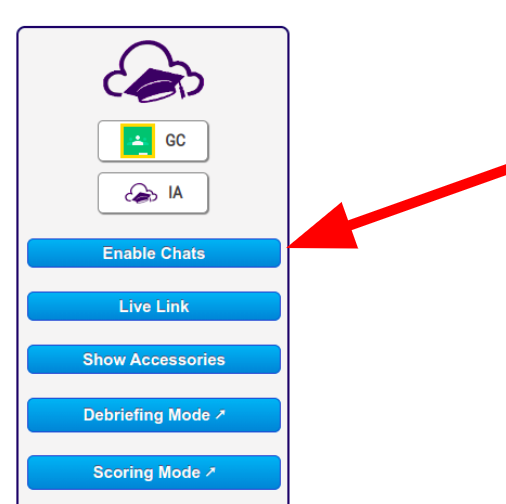

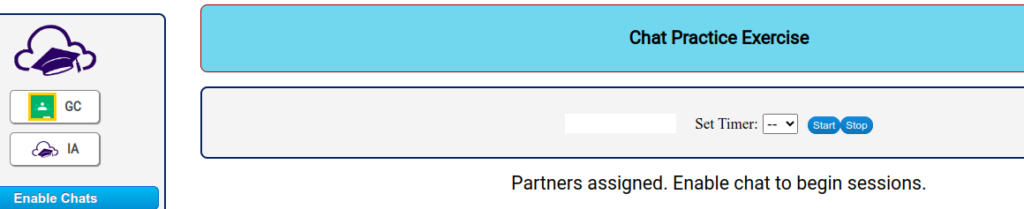

When high security is enabled, the short answer task will close and submit responses if the student gives focus to any other page. The student will be locked out until they are formally re-admitted. Re-admit students from the course playlist using the Task dropdown in the controls on the right of the task.

In addition, short answer and multiple-choice tasks can be locked to certain single-use key codes. Once locked, teachers need to provide each student a different code from the list that was generated in order to allow access to the test. This limits attempts to take the test in situations where students have limited chances.

Further, teachers who need this level of security are encouraged to set time limits on the tasks. This will discourage cheating because it often takes time to look things up. In cases where some students get more time on task, you can set exceptions from the testing modification controls in Utilities. Go to Virtual Classroom and Testing Accommodations.

Tier 2 security can be enhanced by having a proctor with students to prevent accessing other devices. In addition, some schools have screen monitoring software like GoGuardian that can assist in monitoring. Perhaps this would be called “tier 3”?

Why not give Innovation a try in your classroom?