During the pandemic, many office workers moved to remote work from home. This precipitated a rise in monitoring software that companies could use to ensure that, being at home, workers were productive. An article in Forbes Magazine from 2021 reports that “[d]emand for worker surveillance tools increased by 74% compared to March 2019.” This rush to monitor and micromanage turned out to be unnecessary, as fears of a loss or productivity proved unfounded and “94% [of companies] reported that worker productivity either stayed at the same levels or improved.”

But this is not the case with adolescents.

The traditional classroom had to be a “very supervised” place because, by virtue of the fact that they are immature, most of our charges need guidance to get back on track. It is one reason why remote learning went so badly for many youngsters: it is not in the nature of most to be focused. The executive functioning needed to ignore distraction, set goals and reasonable timelines for work, even to break a longer task up into smaller, achievable segments is rarely present in adolescence. Until this develops, the role of the instructors includes teaching this skill and guiding students to follow the right course. Teaching with digital devices at present has reduced much of this supervisory ability. 21st century learning spaces would come with an array of monitoring and accountability features.

Data […] promotes accountability, but it also puts the student potentially in the driver’s seat and that is what developing executive functioning is all about.

I recall an instance where a student of mine was completing the essay portion of an examination remotely. I was able to monitor his examination in real time using software that shared his screen with me. When I noticed that he was typing sentences that appeared beyond his ability, I was able to google those phrases and find the source he was plagiarizing from online (he had his phone with him to cheat). This monitoring software allowed me a virtual way to simulate normal classroom supervision and to take the natural step of concluding the examination and award no credit.

After the pandemic, I continued using digital tools for student work. My students all had ChromeBooks. I had a student who was clever in taking advantage of a certain doubtfulness about technology by some adults around him. Faced with an incomplete assignment, he would claim he did it and that the app must have “lost his work”. He would claim that it “did not save”. In a traditional classroom, I would have seen his paper and whether it was written on, but the digital work did not include this monitor yet. I adjusted the software for his writing assignments to report when a response was deleted, when a student left the browser page for another, when students pasted text in, and even double-check the server to ensure an answer was saved. These application features returned important accountability assurances that were initially lost when moving to digital devices.

As time went on, my colleagues and I devised further modifications to the software at Innovation. I developed the “proctor” on important apps for testing and writing.

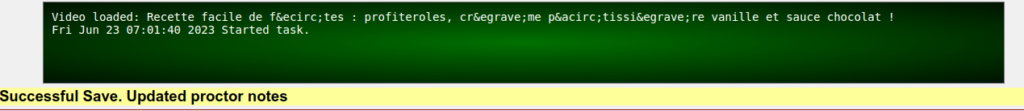

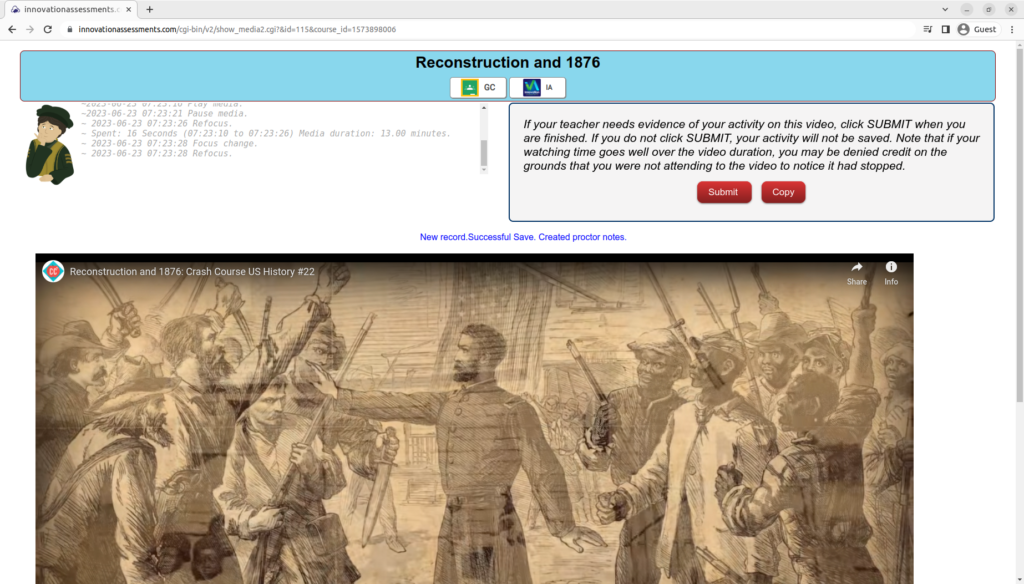

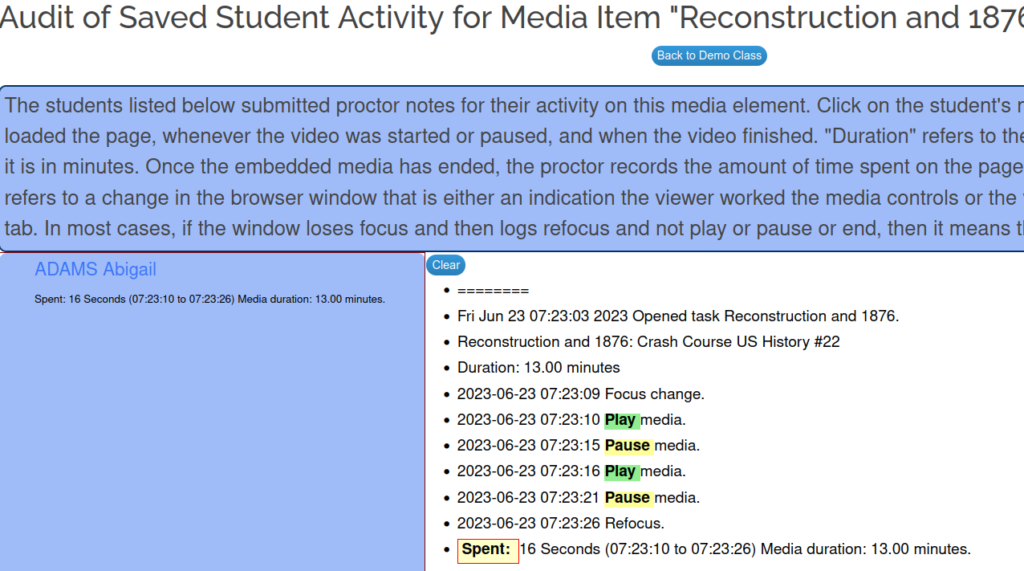

The proctor records data about the page and the students’ interactions with the assignment. Depending on the particular assignment, it records when work has begun, when an ancillary resource like a video has successfully loaded, when a student leaves the page and for how long, when text is pasted in, and when answers are saved. The proctor is visible to students (see illustration above) so they know their work is being monitored.

My colleague in the science department uses a flipped classroom technique. He made a great suggestion for the development of an app to monitor student interaction with a video assignment. As a student watches a video assignment, proctor records events like start video, stop video, how long between pauses, when the video ended, and how long the student was there.

The tracking monitor helped maintain a system of accountability for students.

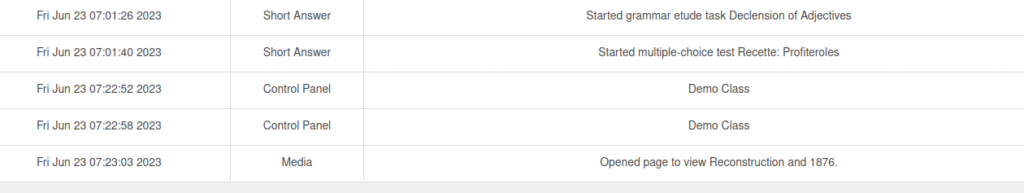

Besides the proctor, Innovation tracks student activity around the site. The auditor maintains a record of logging in, accessing a course, starting a task, saving work, getting a score, etc.

The critical work of developing executive functioning in adolescents can be enhanced by providing youngsters the kind of data that, if they attend to it, can inform their decisions about what they should do. The proctor and other reporting tools are available to all students. Although consequences for missing the mark on attention to task can and should be part of the program, it is not great practice to be all sticks and no carrots. Objective data on what a teenager is actually doing (rather than what they remember they did or want you to think they did) can be the focus of discussions about on-task behavior and how the individual can take responsibility for it. We can take a look at performance on as assignment and examine on-task behavior related to its production. Could on-task behavior have improved the final product?

Data like this promotes accountability, but it also puts the student potentially in the driver’s seat and that is what developing executive functioning is all about.