When I was developing an app for synchronous chat, my eighth, ninth, and tenth graders were only too happy to be my beta-testers. It was in the last month before I was to retire and so I wanted to make good use of my time remaining, especially preparing students for the conversation part of the regional world language examination in French. The chat app arose out of the desire for an effective method for students to communicate in the lesson in a paired situation, in a 21st century learning space.

Synchronous Online Discussion in a Co-located Classroom Setting

A number of advantages to blending online discussion tools in the classroom present themselves. In peer face-to-face interactions, “student differences in social status, verbal abilities and personality traits cannot guarantee equal participation rates (Chinn, Anderson, & Waggoner, 2001, as cited in Asterhan & Eisenmann). High-status, high-ability and extrovert peers may often dominate the discussion and group decision making” (Barron, 2003, Caspi et al., 2006, as cited in Asterhan & Eisenmann). Online discussion tools can reduce these factors and present a more egalitarian framework for participation.

Having students in the same room communicating with each other on a chat system may seem odd at first glance, but in addition to the benefits noted above, there are some practical benefits especially for the secondary level. The presence of an adult will ensure more on-task behavior and more appropriate behavior (no “flaming”, for example). Students may not all have equal access to home internet services such an an asynchronous model would demand. Furthermore, the synchronous model greatly ensures that the task will get done. Asynchronous assignments often fall down to procrastination, a typical foible of the adolescent. A literature review by Asterhan and Eisenmann reveal that “[c]ommunication in synchronous discussion environment is closer to spoken conversation and therefore likely to be more engaging and animating than asynchronous conferencing (McAlister, Ravenscroft, & Scanlon, 2004, as cited in Asterhan & Eisenmann). Students have also been found to be more active and produce more contributions in synchronous, than in asynchronous environments (Cress, Kimmerle, & Hesse, 2009, as cited in Asterhan & Eisenmann).”

When used during the class period, synchronous chat is a small part of a larger lesson which includes scaffolding, participation, and debriefing.

Early synchronous chat software such as reviewed in the study by Asterhan and Eisenmann had some practical limitations for class discussion. Instant messaging or threaded discussion boards both work on precedence by chronology, which makes conversations difficult to follow and so may actually defeat the purpose of the exercise. Some teachers have attempted to use FaceBook or Twitter to facilitate class discussions. These platforms were designed to satisfy a commercial interest.

A 21st century learning space paradigm provides the necessary structure (guardrails and training wheels) to maximize quality participation frequency while eliminating concerns about privacy and advertising.

How it Works

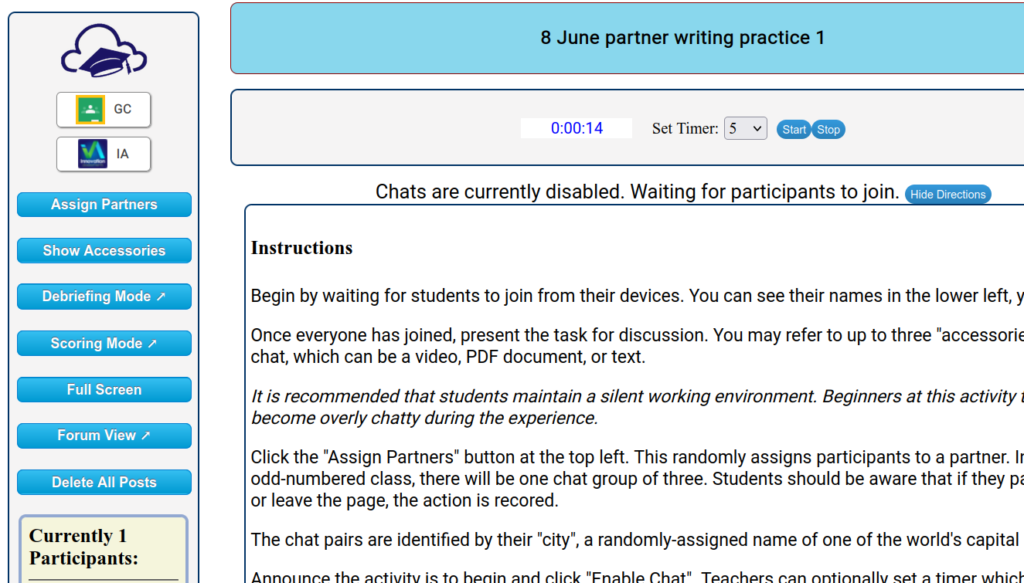

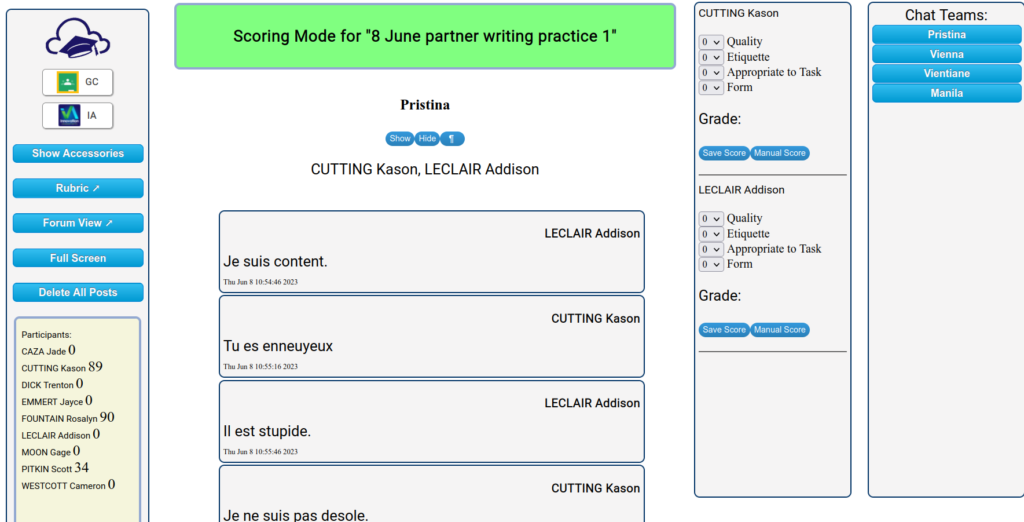

The chat app works like this: the teacher opens a chat session and displays the host control dashboard on the large screen. Next, students join the session from their devices and once everyone is onboard, the teacher explains the assignment. The teacher then clicks the control to generate random partners and then to enable the chat session. A timer can optionally be set. Students engage in a real time discussion to carry out the task for the allotted time. During this session, the teacher can display the current chats going on (anonymously, of course) and offer any coaching that would be useful. At the conclusion of the time, the host closes the chat session and can debrief by displaying the chats and offering comment. The chats are anonymous: unless students introduce themselves in live session, they do not know necessarily who their partner is. The pairs are organized by “city”, a nickname generated by the app to identify them from a list of world capitals.

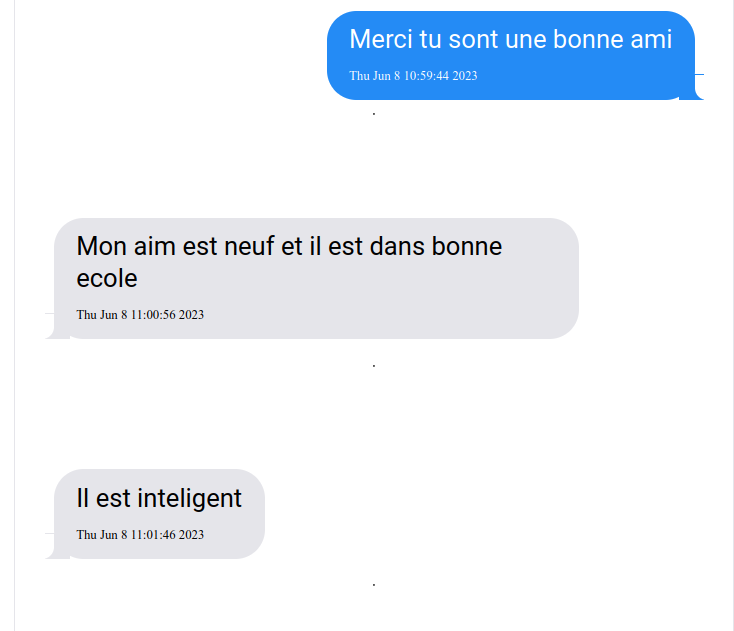

The first issue that developed was that they enjoyed it (not necessarily a problem but…). It caused a lot of “real” chatter in class as students chuckled about funny things others had said or trying to find out who their partner was. Older students who were more serious about their studies also were motivated to communicate outside the chat session to strategize in real time addressing their assignment. My tenth graders were assigned to use the chat as a writing exercise, such that they answered the prompt by collaboratively composing a paragraph. When a class is engaged in this activity, they need to be trained to maintain a mostly silent room, focused on the task and not the distractions.

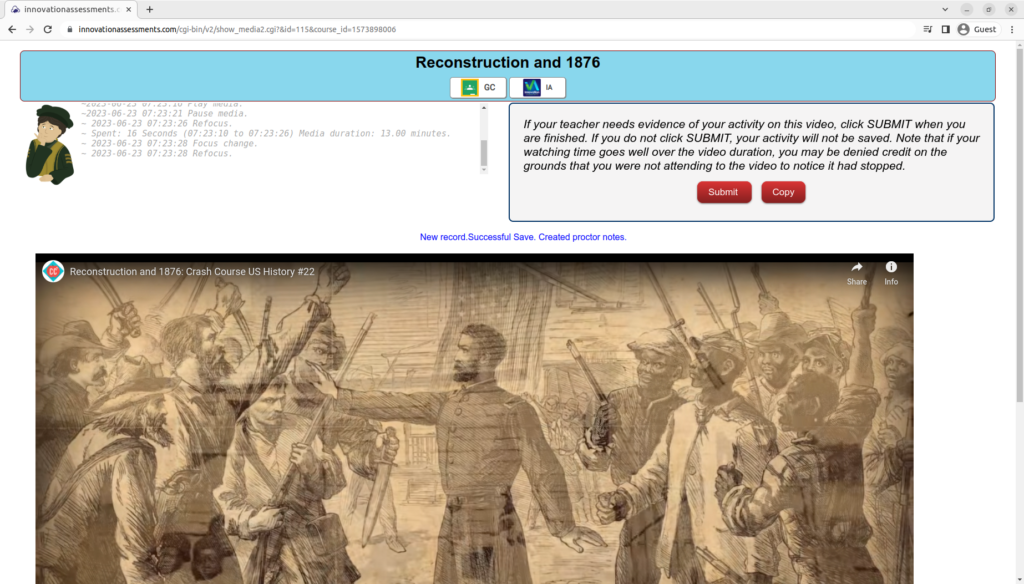

A second issue that arose in the early version of the app was that students would forget the prompt or instructions. It was easy to modify the app to allow the teacher to attach “accessories”: text, video embed, and/or a PDF document with the assignment and rubric displayed. Now students could refresh their understanding of the assignment by clicking a button.

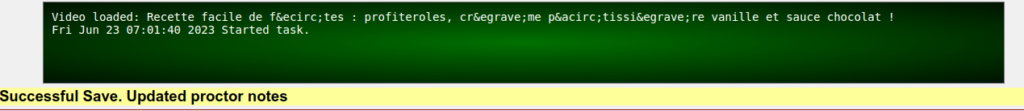

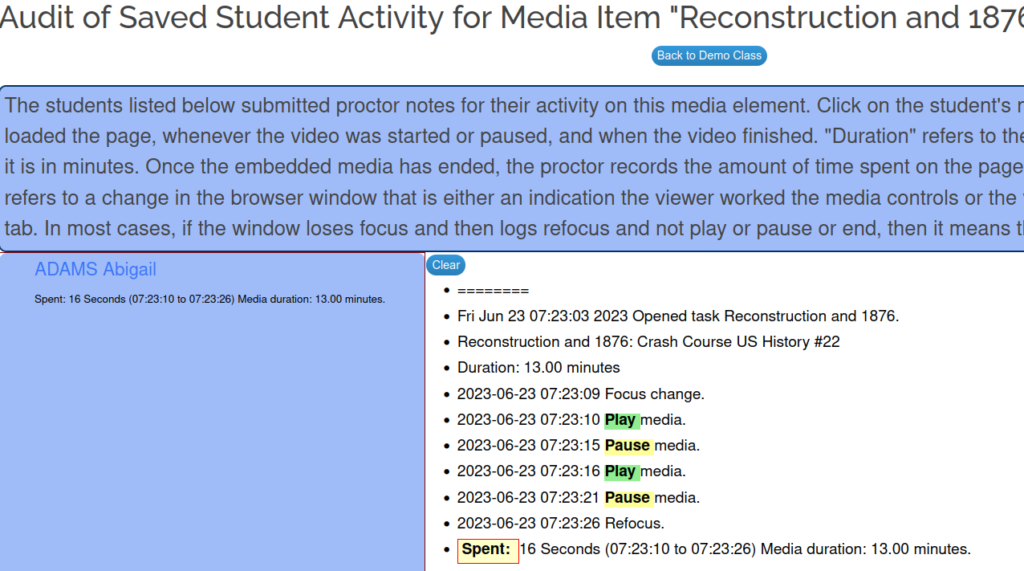

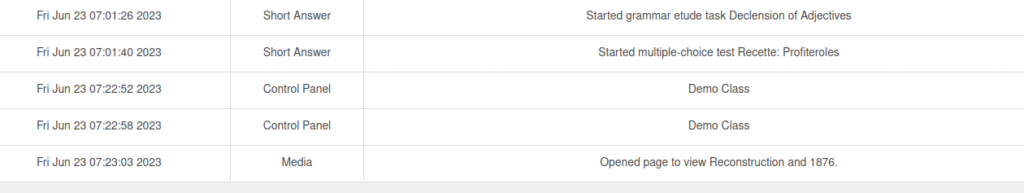

Sometimes a student would leave the chat window to another browser tab to look something up. For situations where is is not allowed, I modified to app to include a “proctor” that records right in the app when a student leaves the window and when they paste in text.

Research on this sort of application support the practice of including assessment in the activity (Gilbert and Dabbagh, 2005, as cited in Balaji & Chakrabati, 2010). Students are aware of the rubric and are graded, which has an enhancing effect on their performance as they are often more mindful of their progress. Using the timer, which displays in the front of the room from the teacher’s host screen is also helpful. If one is pressed for time, one is less likely to be off-task without knowing it.

In keeping with the paradigm of the 21st century learning space, the app lends itself well to assessment and debriefing. The assessment screen makes it easy to assess student work on a built-in rubric.

Students can see their scores and comments.

I developed this in the context of teaching French, but its application to other subjects is clear. For example, a social studies lesson could include a document or video segment for students to analyze or a short discussion on a topic from lecture.

The chat application is designed as a 21st century learning space .

- Guardrails: The proctor for the chat app reports on text paste-ins and leaving the browser tab.

- Training Wheels: The optional accessories can provide the scaffold support for the discussion. The optional timer supports on-task behavior.

- Debriefing: In debriefing mode, anonymized student contributions to chat can be displayed for analysis and discussion.

- Assessment and Feedback: In scoring mode, an efficient system of evaluation saves time and offers students significant feedback.

- Swiss Army Knife: The chat can be viewed in discussion mode, where other features can be applied such as identifying logical fallacies and replying to the posts of students other than one’s assigned partner. In forum mode, the teacher can participate.

- Locus of Data Control: The student chat submissions are stored on a server licensed to the teacher’s control. Commercial apps such as FaceBook and Twitter may be less dedicated to the kinds of privacy and control exigencies of education.

Synchronous chat turned out to be a hit in my French class. It provided a solid and effective tool for engaging everyone in the lesson and made me feel like my time was well spent. In the next academic year (2023-24), I will be teaching an online synchronous college level French course. Look for posts next fall where I share how the new app went over in that class.

References

Aderibigbe, Semiyu Adejare, Can online discussions facilitate deep learning for students inGeneral Education?

C.S.C. Asterhan and T. Eisenmann, Introducing synchronous e-discussion tools in co-located classrooms: A study on the experiences of ‘active’ and ‘silent’ secondary school students, Computers in Human Behavior (2011).